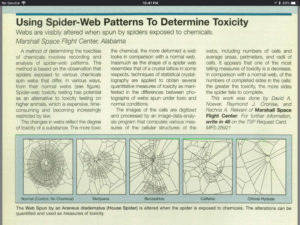

- Using Spider-Web Patterns to Determine Toxicity, Nasa Tech Briefs 1995 No 4 p. 82

Since I’m recovering from jet lag, I’m just going to leave this here and go get another espresso.

Using Spider-Web Patterns to Determine Toxcitiy, NASA Tech Briefs 1995 vol 4 - This Corrosion, 12″ Edition, The Sisters of Mercy. If the article’s got you rethinking your morning habit, never fear — The Sisters of Mercy are here to help.

Friday Fun (10-Nov-2017 edition)

- Sixty Years of Software Development Life Cycle Models, Kneuper, Ralf. IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. The Hegelian account of software development life cycles is apparent to anyone who’s been around for more than a decade, or even worked in different sectors of the industry. In my mind, what Kneuper brings to the discussion in this case is not a simple account of the thesis, antithesis, and synthesis of software development life cycles, but interesting facts about their early development. Prototypes played a role much earlier in lifecycle planning than I think many have been aware of, as was an iterative approach with feedback loops in general.

- The Worst Day Since Yesterday, Flogging Molly. It’s been that kind of a week around here. I highly recommend you go out, get a Guiness, and crank up Flogging Molly as loud as your speaker will allow. You can’t go wrong with that on a Friday evening.

Friday Fun (03-Nov-2017 edition)

- Idea of Order at Kyson Point, Brian Eno. Brian Eno needs no introduction; this is a nice short recent work he put out this year.

- Deep Reinforcement Learning: Pong from Pixels. As promised, here’s a bit of a flashback on reinforcement learning, a neat older result on using reinforcement learning to train a network to play Atari video games. It’s important to recognize in this work, too, just like with the AlphaGo Zero work, that the resulting network does not understand what it’s doing. It can’t explain the rules, doesn’t have any abstractions. It’s just very, very, very good at pattern recognition.

Friday Fun (27-Oct-2017 edition)

- More Than, Au Revoir Simone. Dreamy synthpop at its very best.

- Mastering the game of Go without human knowledge, David Silver, et al; good Nature summary coverage as Self-Taught AI is best yet at Strategy Game of Go, Elizabeth Gibney. This is a very important result, although I think it’s been a little too widely hyped by the popular press as evidence of the coming singularity. Go is an interesting problem domain, because the combinatorial explosion of movies leaves it intractable for traditional game-playing approaches. Reinforcement learning, used by the team, is essentially how humans learn to play go, albeit far, far faster than we learn to play. I am looking forward to seeing discussions in the coming months of the new strategies AlphaGo Zero teaches human players.

Friday Fun! (20-Oct-2017 Edition)

(So, yeah, last week’s promise of a post tomorrow didn’t quite pan out. Anyway, without further ado…)

- Resonant Expanse, Max Cooper & Tom Hodge

I love almost everything I’ve heard by Max Cooper. He takes traditional trance to a whole new level with his use of modulation on minimalist melodies and percussion. This work by he and Tom Hodge is on several of my “music to think by” playlists. - A Preliminary Analysis of Sleep-Like States in the Cuttlefish Sepia officinalis, Marcos G. Frank , Robert H. Waldrop, Michelle Dumoulin, Sara Aton, Jean G. Boal.

The punch line is in the abstract: “In addition, cuttlefish transiently display a quiescent state with rapid eye movements, changes in body coloration and twitching of the arms, that is possibly analogous to REM sleep.” Cephalopods and mammals diverged some five hundred million years ago — like, twice as long ago as when dinosaurs and mammals were hanging together. If this holds true, it’s amazing. I can’t even really call it convergent evolution, because I’m not convinced we can articulate what evolutionary pressures would generate the need for REM sleep in such different ecosystems, unless it’s actually a requirement for brain function. But human and cephalopod brains are very, very different — the common ancestor was probably something like a sea worm with a brain similar to C. elegans. So there’s an awful lot of room for divergent evolution, which we see in things like the gross structures.

Anyway, thinking of cuttlefish and perhaps octopuses dreaming of Max Cooper’s and Tom Hodge’s music makes me very, very happy.

New! Friday fun!

For years I’ve been in the intermittent habit of occasionally sending coworkers interesting things on Fridays that I find on the web. It may be a paper, blog post, or newspaper story that I found particularly interesting that they might not have encountered. Often, but not always, tech related. It might be a paper on ML, a history of computing paper, a blog post on keeping organized or using agile, or something like that. More recently, I’ve added a link to a single song I’d like to share. With both of these I provide a bit of commentary — no more than a few sentences, explaining why I thought this was worth following along.

I’m going to start cross-posting the content here, because there’s never anything proprietary about it, and it occurs to me that it might be of interest to a broader audience.

One remark is in order. I make no apologies that some of what I reference is behind one paywall or another, and no, I won’t send copies of what I link if you can’t access it. I am a member of the IEEE, ACM, and ARRL in part because I value the editorial work they do in their journals and to have access to their digital libraries; the fee I pay for membership in part enables them to do the editorial work that they do. The same goes for the few online news sources I pay fees to access. In all cases, there are ways for motivated non-members to access the works these organizations provide or curate — typically there’s free access for a number of works a month, or the opportunity to buy a reprint of a particular paper at a nominal cost. If what you say really interests you, it’s worth your effort to support the sources that curate that material for you.

Look forward to the first post tomorrow!

SLV Winlink Packet Survey

With help from KE6AFE and WB6RJH, I recently installed a Winlink RMS Packet gateway at the home station in the hopes that having easy access to one would enable me to regularly test my portable packet station — in the past I would assemble one for a specific ARES or public service deployment with bits and pieces, test it, use it for the deployment, and then pieces would be cannibalized for other projects, or software would be reinstalled. Although the topology at the house is not ideal for providing RF coverage, I thought that it would at least be a good exercise, and once set up, I could see if it added anything to the local network.

(I’ll write more about the station configuration in a later post; for this discussion it’s enough to know that it’s connected to a Kenwood TH-D700A radio running 50W into a j-pole on top of the house, but unfortunately below the lip of the canyon we live in.)

San Lorenzo Valley is served by two digipeaters, WR6AOK-3 above the middle of the valley on 145.690, and W6JWS-3 to the northeast on 145.630. In addition, WB6RJH operates WB6RJH-10 on 145.690 above the south half of the valley, with coverage extending into parts of Santa Cruz as well as most of Bonny Doon. Although not in San Lorenzo Valley, W6SCF-10 operates on 145.630, and is accessible from W6JWS-3.

Conferring with KE6AFE, we thought the best thing for me to do was put KF6GPE-10 at my home location running on 145.630, so that’s what I did. Over the month of August, the three of us performed a number of tests at locations known to be of interest during ARES activation, with a bias on Boulder Creek locations because that’s where I live and was most curious about possible simplex paths between Boulder Creek and KF6GPE-10.

I used a Kenwood TH-D72A HT running at 5W to the low-profile magmount antenna on my mobile station for the experiments.

Results were quite good, with redundant relays available at each location. I still need to exercise the WR6AOK digipeater more in both Ben Lomond and Boulder Creek; KE6AFE and WB6RJH provided me with a KA-Node script for relaying through WR6AOK that is more reliable than using plain AX.25 digipeating, but I’ve only tested that at one location. Knowing the regions that remain to be tested it does appear that each served agency location is likely to have access to at least two packet relays through at least two different paths on two different frequencies. Unfortunately, there aren’t as many simplex paths as I would like — as I feared, KF6GPE-10 is essentially unavailable by simplex from anywhere likely to be interesting (other than my living room and Redwood Elementary), and WB6RJH is far enough to the south that simplex at low power is not an option for locations very far north of Felton.

Without further ado, here are the results.

Continue reading SLV Winlink Packet Survey

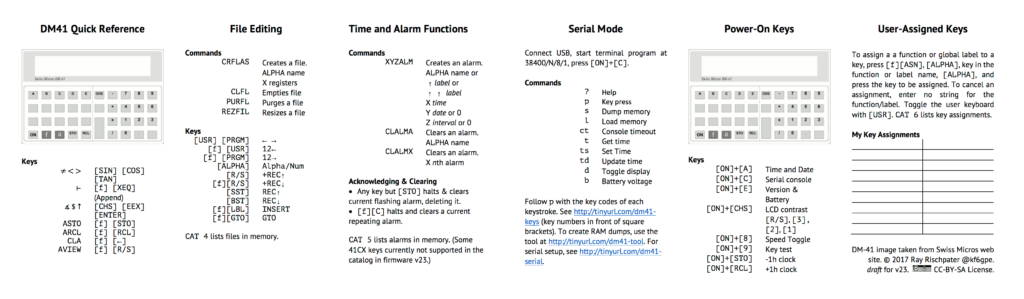

Swiss Micros DM41 Quick Reference

Now that I’ve been using the excellent Swiss Micros DM-41 calculator a while, there are a few things I still tend to forget that are either different than the HP-41CX, or things that are the same that I just never did often enough. The HP-41CX Quick Reference Guide (if you can find one) is really handy, and I’m lucky enough to have an original printed copy in my notebook’s pocket. But there are some specifics to the DM-41, notably the power-on key assignments, that are helpful to have handy.

And thus is born my DM-41 Quick Reference Guide, available under a Creative Commons Share Alike Attributions (CC-BY-SA) license.

It’s formatted to print for trifold to business size, so you can slip it in the business card elastic holder of the DM-41 flip cases.

You can download and make your own from this PDF. I’ve done a limited print run on card stock; if you’re interested in getting one by sending me a SASE, do let me know by email or Twitter (@kf6gpe).

Edit 20-Aug-2017: Updated to indicate that the cards are available for an SASE.

Some notes on the Swiss Micros DM41 series of calculators…

I have a long relationship with Hewlett-Packard portable computing devices; my first experiences programming were on my father’s HP-65, and later the HP-41CV his employer loaned him for his daily work. I had a microcomputer shortly after encountering the HP-65, but learning keystroke programming greatly aided my understanding of assembly language — although I didn’t really recognize that until much later. I later graduated to an HP-28S and then an HP-48SX. In recent years, I have used various HP emulators on the portable devices I use for over ten years; I keep falling back to Free42, because it runs almost everywhere in one port or another. I’ve played with others, and i41CX is what I run on all my iOS devices.

Much has been written about the fine craftsmanship and quality of these early devices — both their physical and electronic design, and the decisions made about their man-machine interfaces. I think exposure to this at an early age definitely has influenced my interest, desire, and recognition of fine design in modern computing products, especially mechanical interactions. I won’t add much here, except that though the bulk of my computation needs now are either so simple that I can do them in my head or on a slide rule (which, yes, I have one on my desk at work) or require real computation to set up, there is still a place for me to use a calculator. It is still faster for me to do some things with a calculator than add formulas to a sheet as I’m analyzing data; once I know what the data is telling me through this exploration, I can then put together the formulas and provide a reasonable presentation. I think because of my upbringing and training, there is something about the cognitive process of using a physical calculator — much as there is in writing with pen and paper instead of typing, a subject much discussed elsewhere.

I have just acquired a Swiss Micros DM41, their small replica of a HP-41CX calculator. It was a bit of an impulse purchase; I have a working HP-41CX I use occasionally, but don’t take it from the house because I am worried about breaking it or having it stolen (my first one was stolen, in 1988). But I had heard good things, and also wanted to support the effort overall — both by encouraging the good engineering of low-volume products for enthusiasts, and in the hopes that by supporting Michael Steinmann and his company that we’ll see other interesting things (the work on the DM42 is an excellent example of this).

I won’t say much about the HP-41 series of devices, but instead provide links to hpmuseum.org and hp41.org. There remains an avid user community, and almost all of the original programs that were published in one way or another can be found on the internet. Many remain useful today. There is also a lot to reflect on when considering the culture of information sharing about calculators and calculation programs in the 1980’s and 1990’s, and blogs and enthusiast sites today about things like iOS and Android, or any programming language, especially the small, up-and-coming ones. More on that in a future blog post, perhaps.

I would like, instead, to capture a few specific things about the DM-41 series (I will refer to both the DM41 and the DM41L as the DM41, because the features I’m discussing apply to both device) that are available from various forums and the Swiss Micros site, but necessarily in one place, both for future users and for future me.

The DM41 is a faithful emulator of the original HP-41CX microcode, running on a low-power ARM processor, with a good mechanical keyboard and dot-matrix LCD display. Battery life and CPU speed is of course drastically better, although the memory remains the same (319 registers plus the stack, or just a touch over two hundred bytes), and at present there’s no way to mount external ROM modules, either as physical hardware or as memory dumps. The DM41 is keystroke-programmed in FOCAL using Reverse Polish Notation, which you either love or will never fully understand. (Contrariwise, it wasn’t until I was about thirty-five that I was able to use an infix calculator with any fluency for more than one operation at a time.) Because the calculator is actually an emulator running the original microcode, synthetic programming is supported. Craftsmanship is excellent — I would not say it is a replica that is identical to the original, but carries the same quality and respect for engineering. The display is good, the keys clicky and reliable (although on the DM41L, take a bit more pressure than on an HP product, but I am told that they break in), and the mechanical design sound. There are two variants of the DM41; the DM41L is in “credit card” format, which is the one I bought, and the other in the HP Voyager format. My only complaint, which is my fault, is that the smaller format is almost too small for my big fingers to use. Had I actually held a credit card and thought about it before ordering, this would not be a surprise, so I fault myself, not Swiss Micros. And having something this small means it’s very easy to carry. Because the physical layout is landscape instead of portrait, the keys are laid out differently; this is a bit of problem for my muscle memory, and my first hour with it recalled my “button paralysis” when I switched from the HP-41 to the HP-28, or the HP-28 to the HP-48, or later picked up Dad’s HP-42S to do something with him in his lab and couldn’t find anything. I have not confirmed this, but it seems that some of the alpha keys are mapped differently, too, or else I have forgotten the mappings for the special alpha characters. Unlike the HP-41CX, there is no shortcut sticker on the back of the DM41L, which is probably a good thing, because it would be very small.

First, without further ado, power-on key sequences for the current (v23) firmware:

Keys Function Description

[ON]+[A] time and date

[ON]+[C] serial console switch to serial console (see below)

[ON]+[E] show information firmware version & battery voltage

[ON]+[CHS] LCD settings change LCD contrast with buttons [R/S],[3],[2],[.]

[ON]+[8] change speed toggle between 12MHz and 48MHz

[ON]+[9] key test key test similar to the one known on the other models

[ON]+[STO] -1h set the clock -1h: daylight saving and changing timezones

[ON]+[RCL] +1h set the clock +1h: daylight saving and changing timezones

Second, here’s how to use the USB port to capture RAM dumps. The original HP-41 series had both card reader and HP-IL accessories for disk (then, “disc”) and tape storage; over the years this has been used to get software off of these devices in a variety of formats. The DM41 series has a miniUSB port, and connecting it to a computer — Mac, Windows, Linux, or even Android with USB-OTG — with the serial mode active gives you the ability to exchange full RAM dumps between the DM41 and the connected computer. Setting up a Mac, PC, or Linux is straightforward, and you can find instructions here. For Android, you can use DroidTerm and a USB-OTG cable. I had it running with my Macbook in about five minutes; most of the time was spent digging around for a USB-C to USB-A adapter.

Once you connect the calculator and terminal (38400/N/8/1, please!), and bring up the calculator in serial mode by pressing C (SQRT) and power, you should see the DM41 prompt in the terminal display. From here, you can enter ‘?’ to get help.

There are two commands you’ll use for memory dumping — ‘s’ dumps the contents of the RAM and pertinent registers to the terminal, ‘l’ takes a similarly formatted RAM dump and replaces the contents of the dump with the calculator. The RAM dump is formatted as printable text; you can copy it and paste it into a text editor. Do yourself a favor — if you’ve spent any time at all programming yours, do a RAM dump now and copy the results to a text file, because it’s easy to forget to do that and later lose the calculator contents while experimenting with uploading other programs. (I speak from experience.)

Where things get interesting is the combination of software available on the web at sites like hp41.org and the programming tool Swiss Micros provides. In this web page, you can paste a well-formatted HP41 FOCAL program listing (no line numbers, though) in the right hand window, and press “encode”, and get a RAM dump you can transfer to the calculator. Even more interesting, you can also install programs you find over the internet that have been saved in the the .raw file format using the programming tool. (You can find .raw files in a lot of places on the Web; a good place for many of the applications that have been written over the years is the library at hp41.org, which only requires free registration). To transfer a .raw program to the calculator, download it to your PC, go to the programming tool, click “choose file” in the raw box, choose the file, and then “decode raw”. Copy the memory dump in the left hand window, go back to your terminal program connected to the DM41, and type ‘l’, and paste in the memory dump.

Because you’re transferring an entire memory dump, if you want to install more than one program, you need to do this:

- Make sure the alphanumeric labels in the program are unique.

- Make sure you have enough memory for the combined programs.

- Concatenate all of the program listings (without line numbers) together in one listing in a text editor, with END statements between each program..

- Copy the combined listing and paste it into the code box on the programming tool.

Press “encode”. - Copy the resulting memory dump and load it into the calculator as usual with the ‘l’ command.

I’ve done this to load the base conversion programs and the phase-of-the-moon program found on hpmuseum.org and the HP-41 User Solutions: Calendars collection.

If you want to get a .raw file from a program you’ve written, it’s likely trickier; I’d start by getting a RAM dump, getting the listing from the programming tool, and then running it through something like the third-party HP User Code utility you can find floating around in a few places. I haven’t tried this, though. If you just want to get your program to another emulator, but you might have problems with the fact that most FOCAL listings include line numbers, and the listings provided by the programming tool do not.

I don’t know a lot about the DM41 memory format, even after looking at some posts on both the Swiss Micros and the hpmusem.org forums (the latter is especially recommended). What’s obvious, though, is that each row consists of four registers in hexadecimal (fifty-six bits per register, separated by spaces), and that it includes some, but not all, of the CPU registers. You’ll see the A, B, C, S, M, N, and G registers, but not the other ones. C is the processor store for the user-visible X register; S is the register holding the status flags. M and N are processor registers for interacting with the X register, as is G (a single-byte register used for alphanumeric mode, I gather). (If you’re interested in the HP-41 internals, there’s a short summary of processor internals at http://www.hpmuseum.org/techcpu.htm, and of the HP-41 memory map at

http://www.hpmuseum.org/prog/synth41.htm). A quick forum post (thanks grsbanks!) helped me understand that the dumps don’t show anything that’s all zeros.

Edits 2017-06-24: Explained missing lines, removed registers not in the HP Nut CPU (I was conflating Nut and Saturn). Minor typo, link fixes.

Two podcasts to check out…

So, the cassette player thing is going well! I have a small stack of tapes from some great musicians on Bandcamp — if I get organized, I may blog about one or two of my favorites over the holiday weekend.

In the meantime, I wanted to share two podcasts with you: Norelco Mori and Tabs Out. Both are reviews of new cassette music releases — but in many ways cannot be more different.

Before I contrast them and make some general comments, I should say of both of these that they are very well produced. Audio quality is high throughout — clear, well-enunciated voices, little background noise, and good diction and speech. From that perspective, both are a real pleasure to listen to. I’m actually pretty fussy about this — I try a lot of podcasts, and don’t stick with many past the first half episode. If the audio is noisy, has too much echo, or if the speaker(s) voice(s) annoy me, off it goes. Similarly, what’s said and how it’s said is important too — we all “um” and “ah” somewhat, but there’s only so much of that — or just plain bad writing or poorly organized thoughts — that I can take before I want to drive into the opposite lane of traffic and put myself out of my misery. Both Norelco Mori and Tabs Out do very well in all of these regards — they’re what I’d call “professional” quality, on a par with good podcasts released by radio stations and other serious podcast networks like TWiT.

They are, however, very different. Norelco Mori prides itself as a podcast with “minimal talk”, and in that it delivers. The host, Ted Butler, does a bit at the beginning telling you what you’re going to hear, and then there’s about an hour of different works, and then a bit at the end about each artist and their method. Because of this, you can listen as actively or as passively as you wish (although I think you get a lot more from it from active listening). I’ve loved everything featured on the podcast, and it’s been difficult not to go to the computer after listening and just queue up a bunch of orders for new music.

Tabs Out is styled more as a radio program a la radio DJs. Honestly, I have a harder time following it; Mike Haley is joined by other hosts, each obviously with a different personality. I’ve never really enjoyed radio programming like that, and I kept wondering when they’d get to the music when I listened to the first episode I downloaded. When they finally do, they pick good music, though. But the format, for me, makes it harder to follow the music and really absorb their selections. It may well appeal to you, though, especially if you’re a fan of traditional radio programming.

If you’d like to discover some new, interesting music with a twist on cassette releases, they’re both worth checking out. I’m finding it easier to discover new stuff this way than surfing Bandcamp or Soundcloud, probably because my on-line time at home is somewhat limited, and I find most music recommendation algorithms just plain suck when it comes to knowing what I’ll like. These podcasts give me a chance to hear some great work by independent musicians when I’m driving to and from work, and their web sites let me follow up with them when I get a chance.